Twelve miles south-east from Chandvad there is a whole town of subterranean temples, known under the name of Enkay-Tenkay. Here, again, the entrance is a hundred feet from the base, and the hill is pyramidal. I must not attempt to give a full description of these temples, as this subject must be worked out in a way quite impossible in a newspaper article. So I shall only note that here all the statues, idols, and carvings are ascribed to Buddhist ascetics of the first centuries after the death of Buddha. I wish I could content myself with this statement. But, unfortunately, messieurs les archeologues meet here with an unexpected difficulty, and a more serious one than all the difficulties brought on them by the inconsistencies of all other temples put together.

In these temples there are more idols designated Buddhas than anywhere else. They cover the main entrance, sit in thick rows along the balconies, occupy the inner walls of the cells, watch the entrances of all the doors like monster giants, and two of them sit in the chief tank, where spring water washes them century after century without any harm to their granite bodies. Some of these Buddhas are decently clad, with pyramidal pagodas as their head gear; others are naked; some sit, others stand; some are real colossi, some tiny, some of middle size. However, all this would not matter; we may go so far as to overlook the fact of Gautama’s or Siddhartha-Buddha’s reform consisting precisely in his earnest desire to tear up by the roots the Brahmanical idol-worship. Though, of course, we cannot help remembering that his religion remained pure from idol-worship of any kind during centuries, until the Lamas of Tibet, the Chinese, the Burmese, and the Siamese taking it into their lands disfigured it, and spoilt it with heresies. We cannot forget that, persecuted by conquer-ing Brahmans, and expelled from India, it found, at last, a shelter in Ceylon where it still flourishes like the legendary aloe, which is said to blossom once in its lifetime and then to die, as the root is killed by the exuberance of blossom, and the seeds cannot produce anything but weeds. All this we may overlook, as I said before. But the difficulty of the archaeologists still exists, if not in the fact of idols being ascribed to early Buddhists, then in the physiognomies, in the type of all these Enkay-Tenkay Buddhas. They all, from the tiniest to the hugest, are Negroes, with flat noses, thick lips, forty five degrees of the facial angle, and curly hair! There is not the slightest likeness between these Negro faces and any of the Siamese or Tibetan Buddhas, which all have purely Mongolian features and perfectly straight hair. This unexpected African type, unheard of in India, upsets the antiquarians entirely. This is why the archaeologists avoid mentioning these caves. Enkay-Tenkay is a worse difficulty for them than even Nassik; they find it as hard to conquer as the Persians found Thermopylae.

We passed by Maleganva and Chikalval, where we examined an exceedingly curious ancient temple of the Jainas. No cement was used in the building of its outer walls, they consist entirely of square stones, which are so well wrought and so closely joined that the blade of the thinnest knife cannot be pushed between two of them; the interior of the temple is richly decorated.

On our way back we did not stop in Thalner, but went straight on to Ghara. There we had to hire elephants again to visit the splendid ruins of Mandu, once a strongly fortified town, about twenty miles due north east of this place. This time we got there speedily and safely. I mention this place because some time later I witnessed in its vicinity a most curious sight, offered by the branch of the numerous Indian rites, which is generally called «devil worship.»

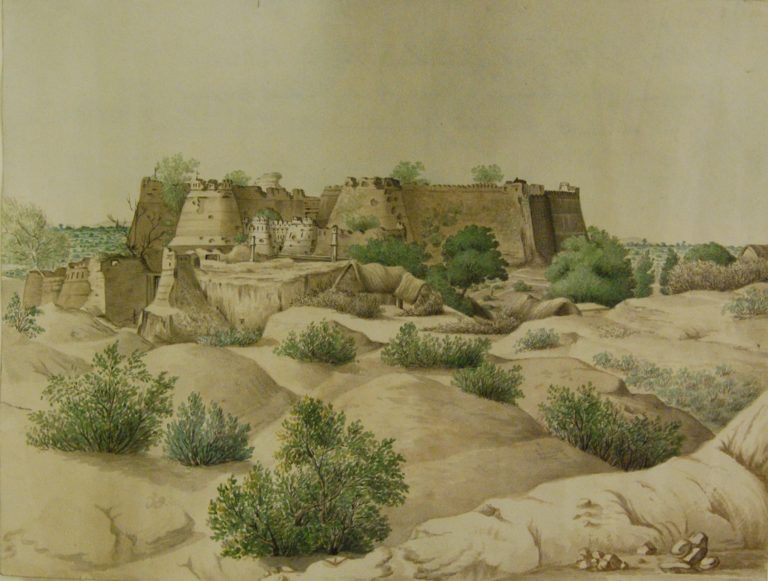

Mandu is situated on the ridge of the Vindhya Mountains, about two thousand feet above the surface of the sea. According to Malcolm’s statement, this town was built in A.D. 313, and for a long time was the capital of the Hindu Rajas of Dhara. The historian Ferishtah points to Mandu as the residence of Dilivan-Khan-Ghuri, the first King of Malwa, who flourished in 1387-1405. In 1526 the town was taken by Bahadur-Shah, King of Gujerat, but in 1570 Akbar won this town back, and a marble slab over the town gate still bears his name and the date of his visit.

On entering this vast city in its present state of solitude (the natives call it the «dead town») we all experienced a peculiar feeling, not unlike the sensation of a man who enters Pompeii for the first time. Everything shows that Mandu was once one of the wealthiest towns of India. The town wall is thirty-seven miles long. Streets ran whole miles, on their sides stand ruined palaces, and marble pillars lie on the ground. Black excavations of the subterranean halls, in the coolness of which rich ladies spent the hottest hours of the day, peer from under dilapidated granite walls. Further on are broken stairs, dry tanks, waterless fountains, endless empty yards, marble platforms, and disfigured arches of majestic porches. All this is overgrown with creepers and shrubs, hiding the dens of wild beasts. Here and there a well-preserved wall of some palace rises high above the general wreck, its empty windows fringed with parasitic plants blinking and staring at us like sightless eyes, protesting against troublesome intruders. And still further, in the very centre of the ruins, the heart of the dead town sends forth a whole crop of broken cypresses, an untrimmed grove on the place where heaved once so many breasts and clamoured so many passions.

In 1570 this town was called Shadiabad, the abode of happiness. The Franciscan missionaries, Adolf Aquaviva, Antario de Moncerotti, and others, who came here in that very year as an embassy from Goa to seek various privileges from the Mogul Government, described it over and over again. At this epoch it was one of the greatest cities of the world, whose magnificent streets and luxurious ways used to astonish the most pompous courts of India. It seems almost incredible that in such a short period nothing should remain of this town but the heaps of rubbish, amongst which we could hardly find room enough for our tent. At last we decided to pitch it in the only building which remained in a tolerable state of preservation, in Yami-Masjid, the cathedral-mosque, on a granite platform about twenty-five steps higher than the square. The stairs, constructed of pure marble like the greater part of the town buildings, are broad and almost untouched by time, but the roof has entirely disappeared, and so we were obliged to put up with the stars for a canopy. All round this building runs a low gallery supported by several rows of thick pillars. From a distance it reminds one, in spite of its being somewhat clumsy and lacking in proportion, of the Acropolis of Athens. From the stairs, where we rested for a while, there was a view of the mausoleum of Gushanga-Guri, King of Malwa, in whose reign the town was at the culmination of its brilliancy and glory. It is a massive, majestic, white marble edifice, with a sheltered peristyle and finely carved pillars. This peristyle once led straight to the palace, but now it is surrounded with a deep ravine, full of broken stones and overgrown with cacti. The interior of the mausoleum is covered with golden lettering of inscriptions from the Koran, and the sarcophagus of the sultan is placed in the middle. Close by it stands the palace of Baz-Bahadur, all broken to pieces—nothing now but a heap of dust covered with trees.

We spent the whole day visiting these sad remains, and returned to our sheltering place a little before sunset, exhausted with hunger and thirst, but triumphantly carrying on our sticks three huge snakes, killed on our way home. Tea and supper were waiting for us. To our great astonishment we found visitors in the tent. The Patel of the neighboring village—something between a tax-collector and a judge—and two zemindars (land owners) rode over to present us their respects and to invite us and our Hindu friends, some of whom they had known previously, to accompany them to their houses. On hearing that we intended to spend the night in the «dead town» they grew awfully indignant. They assured us it was highly dangerous and utterly impossible. Two hours later hyenas, tigers, and other beasts of prey were sure to come out from under every bush and every ruined wall, without mentioning thousands of jackals and wild cats. Our elephants would not stay, and if they did stay no doubt they would be devoured. We ought to leave the ruins as quickly as possible and go with them to the nearest village, which would not take us more than half an hour. In the village everything had been prepared for us, and our friend the Babu was already there, and getting impatient at our delay.

Only on hearing this did we become aware that our bareheaded and cautious friend was conspicuous by his absence. Probably he had left some time ago, without consulting us, and made straight to the village where he evidently had friends. Sending for us was a mere trick of his. But the evening was so sweet, and we felt so comfortable, that the idea of upsetting all our plans for the morning was not at all attractive. Besides, it seemed quite ridiculous to think that the ruins, amongst which we had wandered several hours without meeting anything more dangerous than a snake, swarmed with wild animals. So we smiled and returned thanks, but would not accept the invitation.

«But you positively must not dare to stay here,» insisted the fat Patel. «In case of accident, I shall be responsible for you to the Government. Is it possible you do not dread a sleepless night spent in fighting jackals, if not something worse? You do not believe that you are surrounded with wild animals….. It is true they are invisible until sunset, but nevertheless they are dangerous. If you do not believe us, believe the instinct of your elephants, who are as brave as you, but a little more reasonable. Just look at them!»

We looked. Truly, our grave, philosophic-looking elephants behaved very strangely at this moment. Their lifted trunks looked like huge points of interrogation. They snorted and stamped restively. In another minute one of them tore the thick rope, with which he was tied to a broken pillar, made a sudden volte-face with all his heavy body, and stood against the wind, sniffing the air. Evidently he perceived some dangerous animal in the neighborhood.

The colonel stared at him through his spectacles and whistled very meaningly.

«Well, well,» remarked he, «what shall we do if tigers really assault us?»

«What shall we do indeed?» was my thought. «Takur Gulab-Lal-Sing is not here to protect us.»

Our Hindu companions sat on the carpet after their oriental fashion, quietly chewing betel. On being asked their opinion, they said they would not interfere with our decision, and were ready to do exactly as we liked. But as for the European portion of our party, there was no use concealing the fact that we were frightened, and we speedily prepared to start. Five minutes later we mounted the elephants, and, in a quarter of an hour, just when the sun disappeared behind the mountain and heavy darkness instantaneously fell, we passed the gate of Akbar and descended into the valley.

We were hardly a quarter of a mile from our abandoned camping place when the cypress grove resounded with shrieking howls of jackals, followed by a well-known mighty roar. There was no longer any possibility of doubting. The tigers were disappointed at our escape. Their discontentment shook the very air, and cold perspiration stood on our brows. Our elephant sprang forward, upsetting the order of our procession and threatening to crush the horses and their riders before us. We ourselves, however, were out of danger. We sat in a strong howdah, locked as in a dungeon.

«It is useless to deny that we have had a narrow escape!» remarked the colonel, looking out of the window at some twenty servants of the Patel, who were busily lighting torches.